Timeline

1910

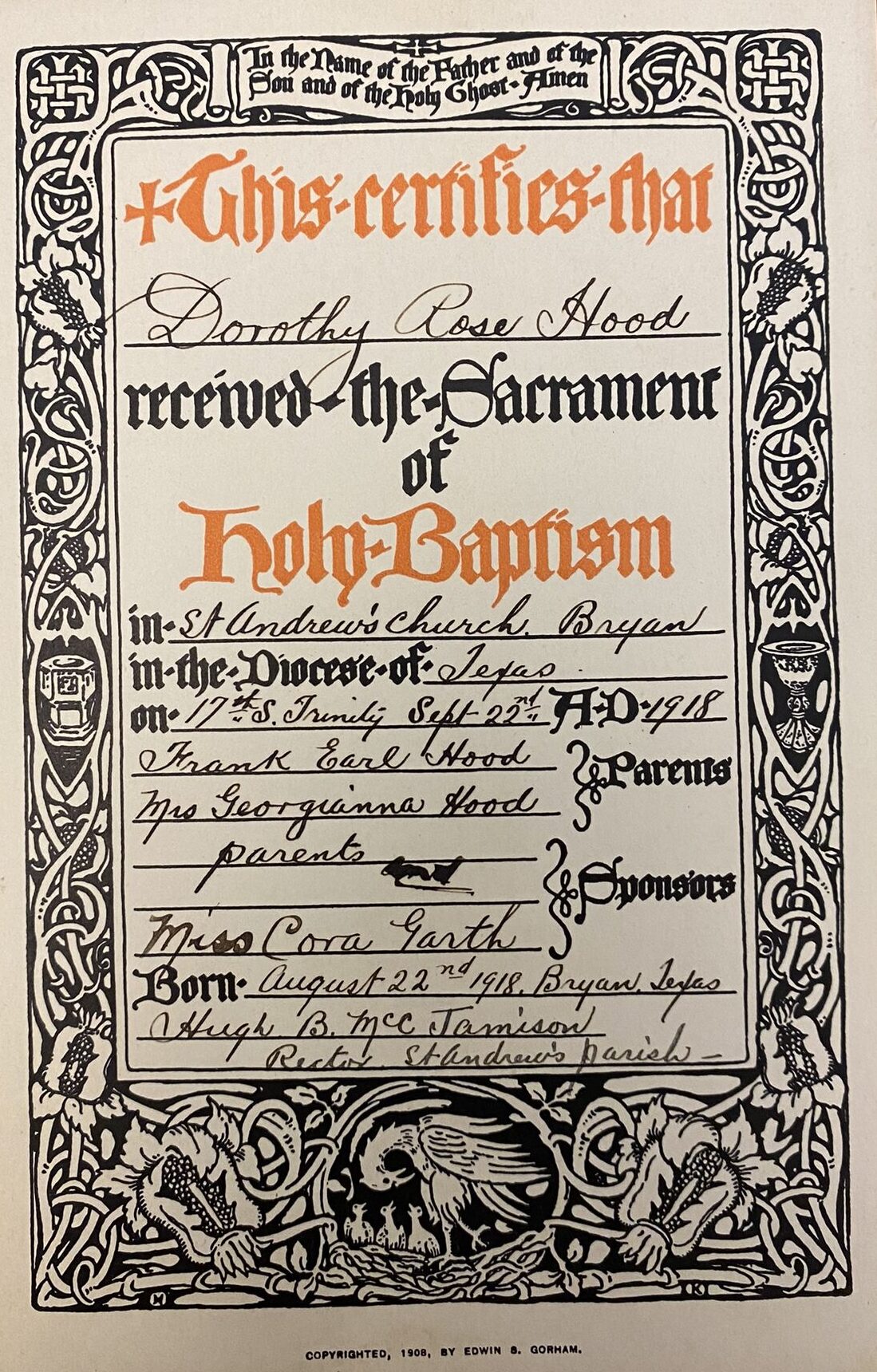

1918

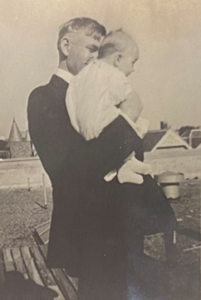

Dorothy Rose Hood was born in Bryan, Texas on August 22 to Frank Hood, a banker, and Georgianna Simpkins Hood. (For many years, this date was misattributed to 1919).

The family moved to Houston when Dorothy was just three months old.

1920

1929

Hood’s interest in art began at an early age. At 11, she took private art lessons along with art classes at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Hood’s parents divorced. She and her mother traveled to Manitou Springs, Colorado, and stayed at the Red Crags B & B Inn. Her mother fell ill with both depression and tuberculosis, and Hood briefly accompanied her mother to a sanitorium. Her father remarried and later had another child, Frank E. Hood, Jr.

Started sixth grade at Albert Sidney Johnston Jr. High School in the fall.

1930

1932

In the spring, Hood graduated from Albert Sidney Johnston Jr. High School. During the summer she was sent to Lake Tippecanoe in Indiana to be with relatives as her mother still battled illness.

When Hood returned to Houston, she came down with severe pneumonia and anemia.

In September Hood entered San Jacinto Sr. High School.

1933

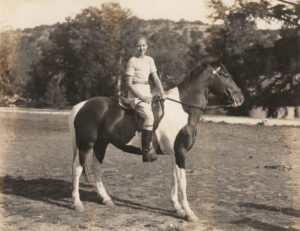

By this date, Hood fully recovered from her illness and she began playing tennis and riding horses.

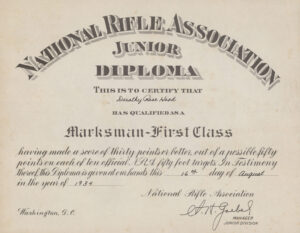

1934

She received a diploma from the National Rifle Association (Junior).

1936

While in high school Hood consistently drew portraits, often using family members as subjects.

Mrs. F. W. Vock, Hood’s art teacher at San Jacinto High School, secretly enters several of these drawings into a drawing competition. As a result, on May, 7, Hood received official notification that she was awarded a National Scholastic Scholarship to the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD),

Providence, Rhode Island. The scholarship covered tuition, but not art materials or living expenses.

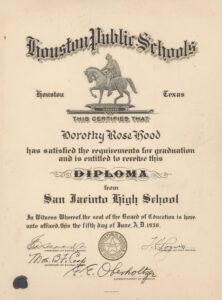

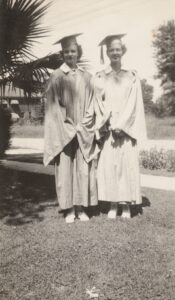

Hood graduated from San Jacinto Sr. High School on June 5. Her father gifted her a blue roadster car as a graduation present.

In the fall, Hood began her freshman year at RISD. During her time there, she studied a range of subjects including ceramics, drawing, and painting. Of her experience, Hood stated, “The favorite kind of painting (my teacher) imposed on students was impossible to impose on me….A Sargent/Velazquez kind of painting that slipped, one slip of color into another. I have always been the other kind, more like a Gauguin/Tamayo, one color against another. I love tapestries. It was a marvelous place to learn about painting, to learn to draw, to become enthusiastic about art. But until I painted on my own, I never learned how.”

1940

The 1940s was a decade of great change for Hood both personally and geographically as she moved and lived in Mexico, Houston, New York, and Central America. Additionally, her art—which she began receiving attention for—shifted dramatically in style. Influenced by a new community of international artists, and the Mexican environment, her drawings and paintings became more abstract, with haunting figures and colors that reflected her a new sun-saturated landscape.

1940

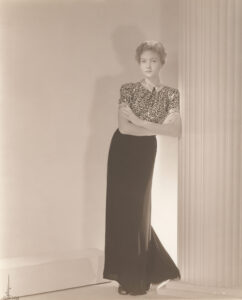

In the spring, Hood graduated from the RISD. She moved to New York to attend the Art Students League in New York, where she studied briefly with artist Morris Kantor and others, before moving back to Houston. During this period, in addition to making art, she worked as a fashion model to pay her expenses.

1941

Hood left for Mexico on a painting trip with two artist friends—Judson Briggs and his wife Rego. They traveled in an old roadster and fundraised the money for their trip by selling “shares”. The dividends of the shares for the investors would be the ability to choose a work of art once the artists returned. Former First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, was one of the investors.

The trip was initially meant to last weeks but Hood decided to stay. Hood lived primarily in Mexico with frequent travel back to the United States as she did not have residency papers in Mexico.

Although her parents helped with financial support, her mother attempted several times to bring her back to Houston permanently.

1942

The drawings ranged in theme from surrealistic explorations of her childhood to haunting impressions of the horrors of war as seen in The Soldier Came to Death as a Misplaced Child, 1942.

1943

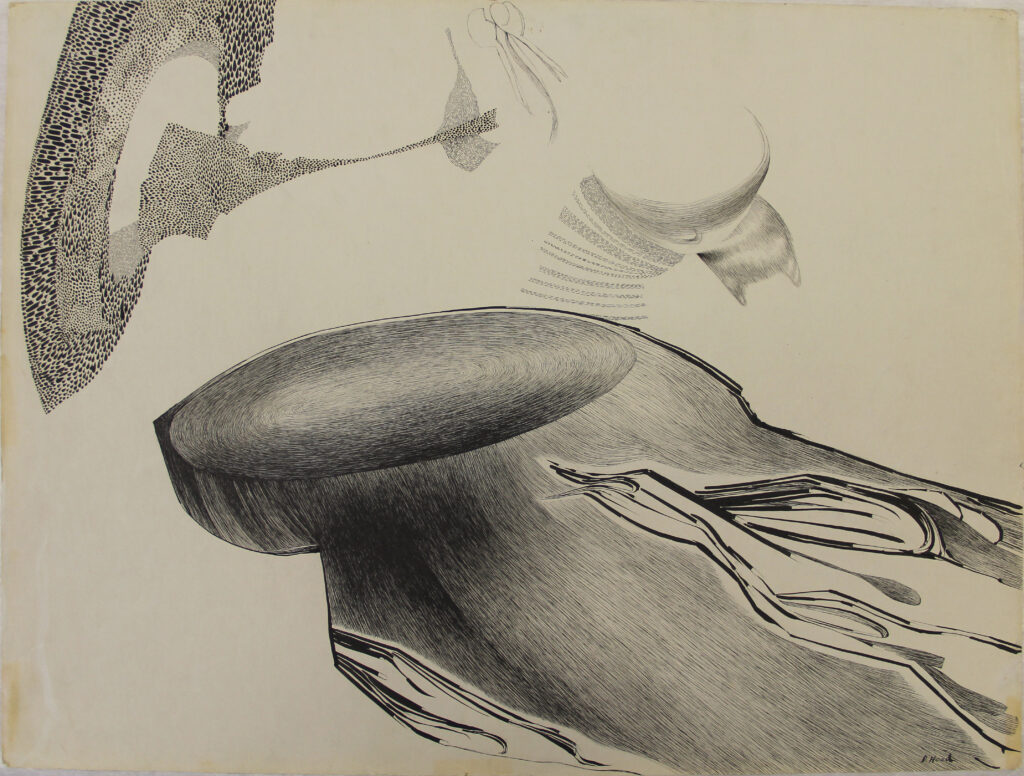

Began working at Madrid 13, which she terms her “first real studio.” Hood created small paintings, but mostly focused on drawings as art materials were expensive. Her drawings span from this period until the mid-1980s.

During this time, Hood interacted with many influential artists and creatives. In addition to the talented Mexican artists, the country had welcomed many emigres who had left Europe due to World War II. Those in Hood’s inner social circle included Spanish novelist Ramon Sender, Mexican muralist and painter, José Clemente Orozco, Belgian writer Victor Serge, Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, American playwright Sophie Treadwell, and the Spanish painter, Remedios Varo. She also encountered Mexican artists, Diego Rivera and Frieda Kahlo, and British surrealist painter Leonora Carrington. Of these, her strongest relationships were with Mexico muralist and painter José Clemente Orozco who became a close friend and mentor, and Ramon Sender, whom she almost married.

Hood had her first solo exhibition in Mexico, The Paintings of Dorothy Hood, at the Galería de Arte María Asúnsolo (GAMA), Mexico City from February 26 to March 12; her friend Pablo Neruda wrote an introductory essay for the brochure, calling her the “Amazon of Manhattan.”

1944

While in Mexico, John McAndrew, Curator of Architecture at the Museum of Modern Art, New York acquires Hood’s drawing, The Seeming Beginning, 1943. McAndrew introduces Hood and her work to his colleague, Curator Dorothy Miller who becomes a friend and champion of Hood’s work.

Brokenhearted from her breakup with Sender, Hood returned to New York. Of the experience, Hood states, “1944 and the beginning of ’45 was the worst winter of my life. Everywhere in New York people took one at face value. My mother had offered to help me in New York. I stayed on 34th Street with my ex-roommate from art school. She was enrolled in classes … But at that time, she didn’t tell me where she was going, or anything for that matter, to ease my newness to the scene.”

1945

Following her time in New York, Hood moved to Connecticut and stayed at the home of playwright Sophie Treadwell, a close friend whom she had met in Mexico.

After a brief stay, Hood returned to Houston where she worked in a Houston shipyard to finance her return to Mexico.

Back in Mexico, Hood met Bolivian composer José Mariá Velasco Maidana. The two traveled around Mexico and Central America and married in May 1945 at the Bolivian Embassy. Of the ceremony, Hood recalled, “Our marriage at the Bolivian Embassy in Mexico City was a nightmare; the Ambassador was late, and the witnesses disappeared. One man was put to use, and sitting and waiting with our friends, this person proceeded to recount all of Velasco’s past loves in detail with a tone of grand pride in his countryman’s and mutual constituent’s, male exploits. Afterward, we all went out to eat, and that was that.” Hood was Velasco Maidana’s second wife.

That summer, Hood accompanied Velasco Maidana to Los Angeles where he conducted a series of concerts of Latin American Music at the Hollywood Bowl beginning on July 23.

1946

Hood and Velasco Maidana traveled frequently to New York as he was asked to conduct a series of six concerts.

1948

In New York, Hood spent time with José Clemente Orozco while he was working in the city. Although she had moved in a different direction stylistically, they remained close. It was the last time she met with him before he died in 1949.

For an unknown reason, Hood moved on her own to Boston for approximately eight months with financial help from her mother. She spent her time visiting museums and studying at the public library. It is here that she first encountered the writings of Indian philosopher Sri Aurobindo, whose thinking greatly influenced Hood’s art.

1950

During this decade, Hood’s reputation began to grow outside of Mexico as she established a relationship with a New York gallery. She began painting on a larger scale, and her works became more abstract. Hood also started playing with textures in her works, altering her technique and adding other materials, such as sand, to the surface of her canvases. In one of the few instances of describing her technique, Hood shared her process in a letter to her gallerist, Marian Willard. She stated, “I the oils, I build up the textures…using an extra top layer of heavier oil, winding or dropping a few strands of paint on the surface, then tossing, as seeds are tossed into the earth, into the heavier oil, a bland crystallizing chemical. Over this is painted the first layer of color which adheres darker to the under edge of the crystalized forms.”

1950

Has her first solo exhibition in New York at the Willard Gallery, from October 10 – November 4.

1953

Hood and Velasco started a new business with the son of Mexico’s Ambassador to Japan, creating silver medallion jewelry. They moved to Puebla, Mexico where the factory was located.

While in Puebla, Hood took French classes.

1955

Hood and Velasco Maidana moved into a new home on Calle Sinaloa, Mexico City.

1956

The next year, the two moved to New York for a few months where they lived in an apartment on West 22nd Street for $90 a month. Not long after, they relocated to Mount Vernon, New York where Velasco Maidana continued with the medallion jewelry business. While in the city, Hood spent much of her time visiting museums and galleries.

1957

Nominated for Art in America’s “New Talent in the U.S,” on the recommendation of MoMA curator Dorothy Miller.

1958

Wanting to return to Mexico, Hood began teaching crafts such as mobiles, kite-making, and papier maché projects to children in Mount Vernon to raise money.

1959

Before returning to Mexico, Hood and Velasco Maidana lived for several months with her mother in Houston.

While in Houston, Hood had her first meeting with gallerist Meredith Long.

Once back in Mexico, Hood and Velasco Maidana settled in the San Angel district. About this location, Hood stated, “Inside the house, the last in Mexico at Calle del Secreto in San Angel, great walls closed off each neighboring garden, and we observed the passing life of past ministers of state easing out in their limousines.”

1960

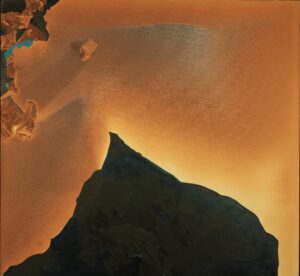

Feeling that “it was the end of the road in Mexico for a foreigner,” Hood returned to Texas in the 1960s. During this decade she formed new relationships in the emerging Houston art community, occasionally attending various exhibition openings of other artists’ works. Despite this sporadic participation, Hood still felt isolated, partly because she was one of the few women in the artistic community and also due to what she perceived as a competitive spirit among them, unlike what she experienced in Mexico. She explained that Houston artists, “had a strange quality of not helping each other. It alienated me. I had never seen anything like that…There was too much competition between all of us.” Yet, through the efforts of her gallerist and the contacts she made, she found support for her work. Hood established herself as a force within the Texas art scene with solo exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Witte Memorial Museum, San Antonio. She also began teaching, becoming a guide and inspiration for generations of future artists. During this decade, Hood’s paintings became bolder, steeped further into mysticism, and radiate energy as seen in Earth Bound Heaven, 1963.

1960

Hood exhibited her work for the first time with Meredith Long who arranges the exhibition Dorothy Hood, in his Houston Galleries in Dallas from April 15 –30, 1960. Long became Hood’s primary gallerist and she continued to have regular exhibitions with the gallery until 1986.

Throughout the 1960s Hood engaged in ongoing correspondence with the reclusive Surrealist artist Leon Kelly (American, 1901–1992); his advice helped her understand and navigate the art world and pushed her further explorations into spiritual realms.

1962

By April, Hood finalized plans to leave Mexico permanently, in part due to the care needed after Velasco Maidana began displaying symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and could no longer conduct. They moved to Houston.

1963

Joined the faculty of the Glassell School of Art, the Museum School of the Museum of Fine Arts Houston where she taught painting and drawing until 1972.

During this period Hood spent time at NASA and formed relationships with both scientists and astronauts. She began creating paintings that explored the universe along with her Outer Space series of drawings that illustrated the cosmos and the outer reaches of the mind and imagination. Hood continued to work within this series through the 1980s.

1968

Hood’s mother, Georgianna, died on January 27, leaving Hood a monetary inheritance along with stock in General Motors.

1969

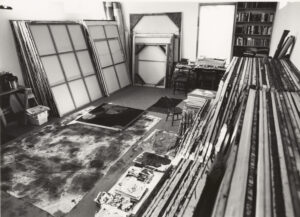

Sebastian “Lefty” Adler, Director of the Contemporary Art Museum, Houston, rented a studio building behind the museum for Hood to create work. He encouraged her to create large canvases and because she had the space, she was able to do so. This catapulted Hood’s work into new realms. For Hood, working large and ‘The discovery of what I can do in them is the most important thing that ever happened in my painting life.’

1970

The 1970s were a pivotal period for Hood both personally and professionally. During this decade she formed significant relationships that opened her to new experiences and opportunities. With her first large-scale retrospective, her career flourished, with numerous museum and gallery exhibitions and works added to the museum’s collections. Awards and commissions followed, and she began showing her work in Europe after winning a travel grant. Hood began working on two major series of paintings, including Sea Elegy and her African opus. Her paintings increased in scale, her color juxtapositions became more striking. and her forms took on strong, but visceral qualities—all putting on full display her confidence in her ideas and techniques as seen in Dancing and Gold.

1970

Installation of Hood’s exhibition at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston

1971

She participated in The Larger Canvas: 5 Houston Artists Commissioned by Houston National Bank, Billboard Project. The billboards dotted the Houston landscape from May 16, 1971, to May 15, 1972.

1972

Hood took up sailing in Galveston Bay. Her time on the water inspired her Sea Elegy series and other works even into the 1990s that explore the ocean and marine life such as Wave V, 1997.

The Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, New York opened Dorothy Hood’s Paintings, a large, mid-career retrospective of her paintings on July 6.

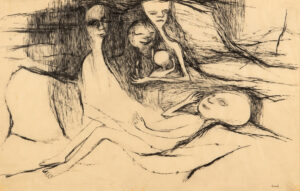

Around this time, Hood’s drawings began to shift in style; she was in the beginning stages of a neck injury that became full-blown over the next few years. To accommodate the pain she felt when standing and working over her paper in a tightly, detailed fashion, she began to work more loosely as seen in My Mother. In this drawing, Hood excavated her surrealist roots and combined them with her desire to explore her complex relationship with her mother.

1973

The American Academy of Arts and Letters in New York awarded Hood the Childe Hassam Purchase Prize for her painting, Zeus Weeps. This work of art was later gifted to the Blanton Museum, University of Texas, Austin.

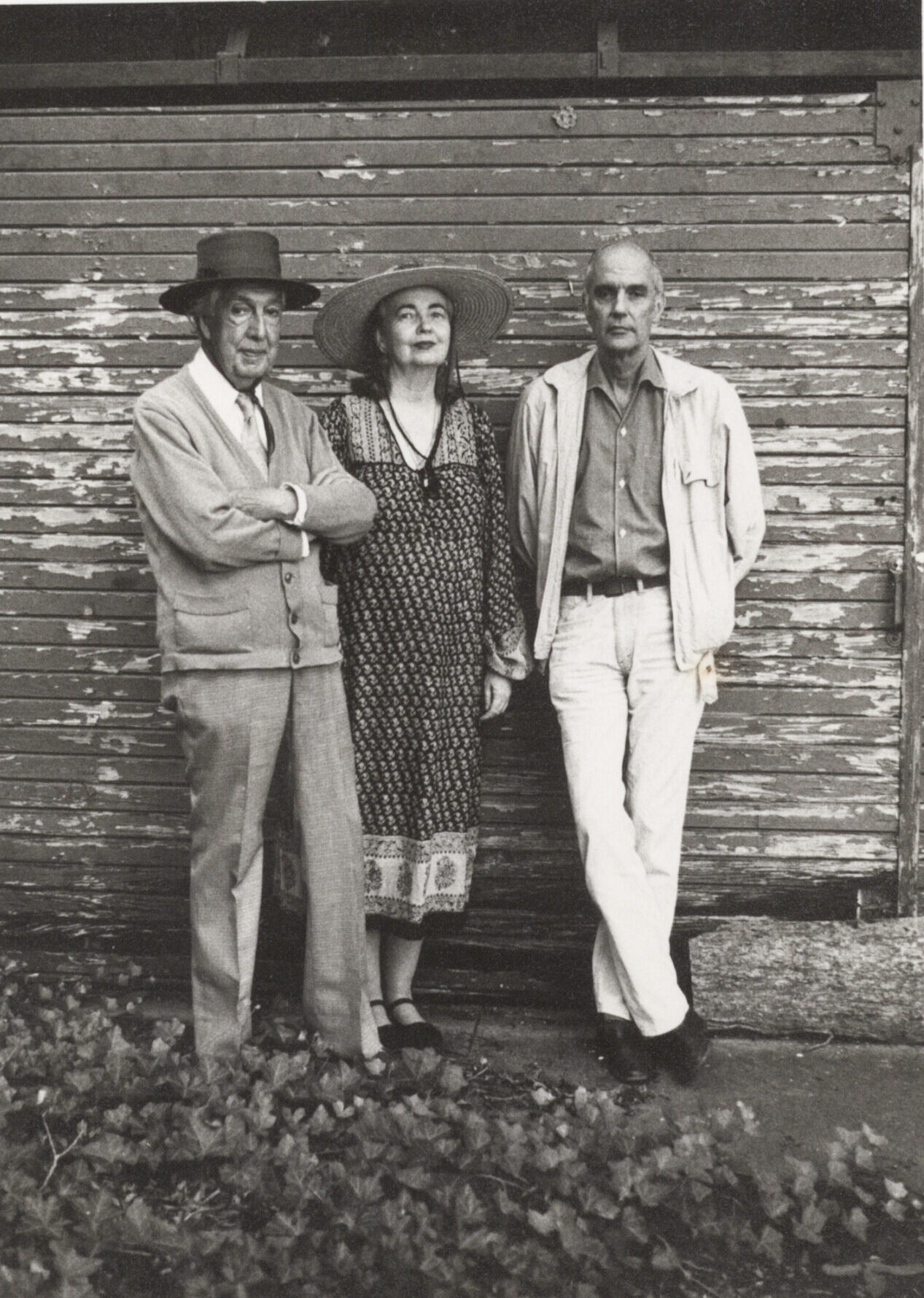

Hood was awarded a Brown Foundation Travel Grant to travel on a European tour. This was her first trip to the continent, and she visited London, England, and traveled to Nice and Paris in France and met with several artists in their studio including Mark Tobey. While in Basel, Switzerland, Tobey introduced Hood to writer and art enthusiast Baron Krister Kuylenstierna, who became a close confidant and “the great love of her life.” Kuylenstierna introduced Hood to Swedish art collector and patron Theodor “Teto” Ahrenberg.

1974

The Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, New York once again featured Hood in a solo exhibition, organizing an exhibition of her drawings which traveled to three additional venues.

Ahrenberg invited Hood to work at his Atelier in Chexbres, Switzerland. After this initial outing as an artist-in-residence at the Atelier, Hood returned for three additional periods between 1974 and 1979. While at the Atelier, Hood met other artists including Christo.

After finishing her time at the Atelier, Hood met up with Kuylenstierna and traveled with him to Paris, France, and Venice, Italy.

La White Gallery, Lausanne Switzerland included Hood’s art in their booth at the Basel International Art Fair from July 19-29.

She received a commission from James Talcott, Inc. to create a painting integrated into the computer panels of an IBM machine.

Became a member of the National Society of Literature and the Arts.

On August 26, the Houston Ballet commissioned Hood to create the sets for Allen’s Landing. The ballet debuted in 1975.

1975

Hood participated in the Visiting Artist Program at the School of Art, Syracuse University from October 29 to December 18.

From May 24 to June 23, Hood once again worked at Ahrenberg’s Atelier in Chexbres, Switzerland. Afterward, Hood traveled to Rome, Italy, and Madlio, Spain with Kuylensteirna.

1976

Hood ventures into set design for a second time, when she is asked to create the sets for the play, Royal Hunt of the Sun, presented at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto.

During the Spring semester, Hood takes a sabbatical from teaching at the School of Art MFA Houston; she undergoes surgery in April for an unknown ailment.

At this time, Hood began to experiment with watercolor painting.

In May, she traveled to Lima, Peru with Velasco Maidana.

1977

Colorado State University asks Hood to be a visiting artist from April 4-6.

During this period, Hood struck up a friendship with visual art critic Clement Greenberg. Although their relationship is conducted primarily through correspondence that lasted through 1985, he became a meaningful confidant.

Visited Montreal, Canada, and spent time with Kuylenstierna.

1978

The Houston Museum of Fine Arts lends Hood’s pen and ink drawing, Warrior’s Plumage, 1957, to the home of the Vice President of the United States (Walter and Joan Mondale) in Washington D.C. for one year. On August 2, Hood dined with the couple.

1979

In April, Hood participated in an artist residency at Tamarind Institute in New Mexico. While there she worked on a series of seven lithographic prints with master printers Stephen Britko and Jefferey Sippel. She also lectured at the University of New Mexico.

On May 18, the Accademia Italia delle Arti e del Lavoro (Italian Academy of Arts and Works) conferred upon Hood the honor of Gold Medal Academic.

Hood and Velasco Maidana, accompanied by Kuylenstierna, traveled to Bolivia in celebration of Velasco Maidana’s 80th birthday.

1980

Hood’s success continued in the 1980s. She settled into a permanent home and studio and brought in help to care for Velasco Maidana, whose health continued to decline. Hood continued traveling, and in her art, she expanded her means of expression by experimenting with the medium of collage. At the same time, she reached a mature sensibility in her drawings and paintings. Still exploring both inner and outer realms, her works are simultaneously elegiac and ecstatic.

1980

Art Journal invited Hood to submit an article for their summer issue. In “Sighting The Invisible Frontier,” Hood elucidated her ideas about the importance of the void in art. For Hood, the void symbolized the deep subconscious, where fears, lived experiences, and memory combine to become the impetus for creation.

Upon the death of her aunt, Dorothy Norwood, Hood received her aunt’s home and its contents. She was also bequeathed stocks in Bethlehem Steel, Standard Oil, half of her aunt’s General Motors stock (291 shares), along with the balance of Norwood’s savings and checking accounts. Hood moved into this home, expanded it to contain a studio, and continued to live there for the rest of her life.

1981

Hood traveled with Kuylenstierna to Greece and Egypt, where she encountered Arabic and Chinese book illustrations, newspapers, and various fabrics. These materials sparked her imagination and led to her starting to work with collage, a medium that she found great joy in working with and continued to explore until the end of her life.

On September 29, the Universita Delle Arti, Italy, conferred the Diploma of Merit on Hood.

1982

Hood was elected a member of the Italian Arts and Letters.

She had work selected, once again, for hanging in the official residence of the Vice-President of the United States (George H.W. Bush), in Washington D.C.

Hood was featured in the documentary film Works by Women: From the Heart, which explored 13 artists from the Gihon collection. Other featured artists included Lynda Benglis, Nancy Chambers, Clyde Connell, Janet Fish, Hermine Ford, Mary McCleary, Gail Stack, and Dee Wolff.

In November, Hood traveled to Greece to meet up with Kuylenstierna. His plans changed so she explored the area on her own.

1983

Received the Mayor’s Award for Outstanding Contribution as a Visual Artist at The Mayor’s International Houston Festival Ball.

Participated in the Images of Texas Symposium at the Amarillo Art Center, held on September 23–24.

1984

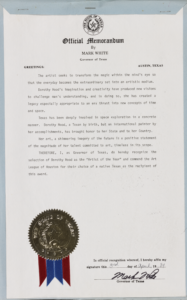

On April 3, Hood was recognized as the artist of the year by the Art League of Houston and the Governor of Texas, Mark White.

In July, Hood once again traveled to Greece.

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey selected Hood as a finalist for an art commission for Terminal C at Newark Airport.

1985

Hood was the subject of the documentary film Color of Life, jointly produced by Pamela Peabody, Caroline Farb, and the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and directed by Carl

1987

Baron Krister Kuylenstierna died.

1988

On February 10, Hood received the Outstanding Achievement in Visual Arts Award from the Women’s National Caucus for Art for a lifetime of distinguished professional achievements.

1989

On March 19, the Texas Commission on the Arts recognized Hood for her contribution and dedication to the arts in Texas.

Hood loaned work to the United States Art in Embassies program, which displayed her paintings in United States Embassies in Madrid, Spain, and Singapore.

On November 15, she legally established the Dorothy Hood Foundation.

On December 6, Hood’s husband, José María Velasco Maidana died at home from Parkinson’s disease.

1990

After losing two significant people, her husband, José Velasco Maidana, and the love of her life, Krister Kuylensteirna, Hood, in the 1990s, found strength in a new relationship. In pursuit of spirituality and enlightenment, Hood visited India multiple times. In the second half of the decade, she faced mortality, once again, as she battled cancer. During this period Hood continued to complete large, complex, and powerful works, such as Going Forth IV.

1990

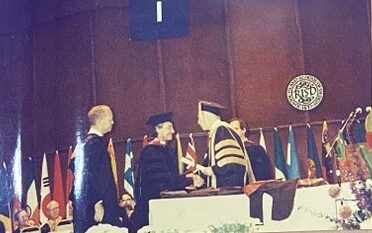

On June 2, Hood was awarded an honorary doctorate from the Rhode Island School of Design.

Hood traveled to India with her close friend, the geneticist Dr. Krishna Dronamraju. It was the first of many trips to India and they returned in 1993, 1994, and 1997–1998.

1993

In a letter dated January 6, Governor Ann Richards nominated Hood for inclusion into the Texas Woman’s Hall of Fame.

1994

Visited Kalakshetra Foundation College of Fine Art, in India with Dr. Dronamraju on August 8; Hood also traveled to Madras, and lectured to the Artist’s Handicrafts Association, on August 7.

1995-1996

Hood experiences a falling out with her half-brother, Frank E. Hood Jr. which is never repaired. In a codicil, Hood removed him as a beneficiary in her will.

During this period, Hood was diagnosed with breast cancer. To treat the disease, Hood had both a mastectomy and chemotherapy. After her diagnosis, she returned to painting smaller canvases, while continuing to work with collage.

2000

2000

On October 29, Hood died from breast cancer at age 82.

2001

The Art Museum of South Texas in Corpus Christi acquired 280 paintings, 160 drawings, and 400 collages from the Hood estate. To complete the acquisition, the Museum settled Hood’s outstanding medical expenses. Since acquiring the material, the Museum has consistently exhibited Hood’s work every year in long-term installations in the Permanent Collection Galleries, individually curated one-person exhibitions, or through inclusion in group exhibitions from the Permanent Collection.

2010

2016

2019

The Art Museum of South Texas donated the Dorothy Hood papers along with the personal papers of her husband José María Velasco Maidana to the University of Houston Special Collection Library. The Dorothy Hood papers were cataloged and archived, and are available to students, scholars, and the public, through the UH Special Collections. Within the archives are personal papers, prolific correspondence, scrapbooks, photographs, journals, catalogs, artifacts, audio/video recordings, and ephemera documenting Hood’s life and career.

McClain Gallery in Houston became the primary representative of Hood’s estate.